Home

The History Of Cider Index

by Rebecca Roseff; 2007

Medieval References to Cider;

Medieval References to Orchards;

Post Medieval Orchards;

Scudamore and

Redstreak;

John Beale;

John

Evelyn;

Orchards in the 19th Century;

The Extent of Orchards;

Orchards today;

Planting and Yields;

Pests and Spraying;

Orchards and Wildlife;

Mistletoe;

The Noble

Chafer;

Moths

Cider is made from apples, which are grown in orchards, so

to begin at the beginning, when did orchards begin? To answer this we must turn to

archaeology and pollen diagrams. We know that Crab apples (Malus sylvestris

ssp sylvestris) came naturally into England after the retreat of the ice,

around 10,000 years ago. Crabs are quite rare trees, most that we see in our

hedgerows today are actually wildings, grown from pips from a cultivated apple (Malus

sylvestris ssp mitis). The native crab has always been rather

mysterious, usually found as a single tree in the middle of a wood, which is

curious as each tree produces thousands of seeds. Here is a possible

explanation.

“…It does appear that trees in nature, if you look at it,

aren’t solitary plants, they like to be in a forest situation, a clump

situation. I think the reason for this is that it gives a kind of natural

support to each other, the plants will stop the wind coming in. When we planted

the orchard at 400 trees/acre they grew a lot faster and better than at 280

trees/acre. They cropped after five years which is normal but then we found

that they were all searching for light, in as much as they had created a large

canopy, so no light was penetrating down to the ground, no light was coming in

left or right of the tree, so the only way the trees could look for light was to

go up, so we got vigorous growth of the tree shooting up to 20/25 foot which was

then creating more problems. Because less light was getting in and the apples

of the lower branches of 2 foot 6 off the ground were very, very small,

unacceptable size for cider fruit, and the ones on the upper branches were a lot

larger. So then we had to have a massive clear out of the top branches

chopping, chopping about 6 foot off the top branches reducing the tree right

down to a size and keeping it at about 15 to 20 foot. So that’s one of the

problems, you’ve got a lot more work to do with the pruning and with the

looking after it. It’s not an easy orchard, I wouldn’t do another with 400

tree/acre”

Jim Franklin,

Orcharder, 2006

Apple pips and charred remains have been found on

archaeology sites from the Neolithic (c 4000 BC) onwards, but it is generally

assumed they represent crab apples. Later on, writing from the Greek (circa

900 BC to 400 BC) and Roman period (circa 400BC to 400 AD)

show that people had by then developed cultivated apples. These almost

certainly came from a different species to the Crab Apple (Malus sylvestris).

The home of the dessert apple (Malus domestica) is thought to be

Kazakstan and they were probably introduced into Europe in prehistory. Roman writers such as

Varro (116-27 BC) Columella (4-70 AD) and Pliny (23-79 AD), describe growing,

storing and selling apples and pears, and there were several varieties. It is

impossible to distinguish a cultivated apple from a crab though from pips or

pollen. It seems reasonable to assume that if people were able to cultivate

wheat from 4,000 BC, they must have learnt also how to encourage orchards, for

fruit and cider.

(For more on origins of the apple click

here).

It is not until the medieval period (circa 1000 AD

to 1500 AD) that documentary records refer to orchards and even then, there are

very few. The national Access to Archives (A2A) website lists documents from

County Record Offices across England. A2A is a selection of documents, not the

totality, and the catalogue depends on what the individual cataloguers

considered important, so if they didn't catalogue the word orchard or cider it

will not appear. Nevertheless A2A contains a large and representative

sample of English documents. The National Archives (TNA) has a more

comprehensive catalogue (over 10 million entries) of documents that have become

part of the national collection. The two catalogues together therefore gives a

big sample of documents, but certainly not the totality.

It maybe that in the medieval period cider was called wine

by some because searching the two databases for cider reveals surprisingly few

references before 1450, so few in fact they are worth listing (plus a few

brought to my attention by James Crowden from other sources)

-

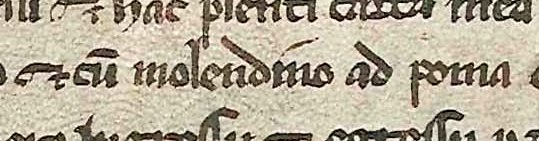

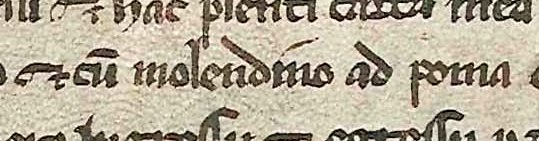

Staffs, 1200, a house called Pressurhus with

outbuildings including a cider press (molendina ad poma) (D948/3/80

Reproduced Courtesy of Staffordshire Record Office)

-

Hampshire, 1270, a quitclaim which included 1 tun of

cider and a quarter of corn per annum with use of lands for one life time

-

1275 Sale of cider Battle Abbey, Sussex

-

1275 Cider made in Yorkshire

-

Warwickshire, 1276, 20s for payment for cider at

Wootton Wawen,

-

1291, cisera in Shaftesbury Abbey accounts (Dorset VCH)

-

1297; church's tithes of corn and cider for the rector

of Combe in Tynhide Devon (C241/32/283)

-

1301, Shapwick, Somset, cider produced on the demesne (VCH,

Somerset, Vol 8).

-

1305, Westonzoyland, Somset, 35 qtrs of cider apples

(VCH, Somerset Vol 8).

-

1313 Meare Abbey Somerset, garden produced apples for

cider (VCH Somerset Vol 9).

-

1340, tithes of cider in parish of Beaminster (Dorset

VCH)

-

Cornwall, 1341, purchase of cider in a list of victuals

bought

-

Sussex, 1349, expenses for buying and carriage of cider

(cisere) to Shoreham, (TNA)

-

Devon, 1358, sale of cider at Sampford Peverell

-

Devon, 1383, reference to cider (sicer), collecting

apples in a garden, carrying to presser, hiring a presser to make two casks

of cider, milling apples and carrying home two casks of cider.

-

Devon, 1451, reference to cider at Kingskerswell Manor

-

Ed IV (1461-1483); “A vessel named the Mavye of Reyle,

brought into Poole as part of its cargo 1 pipe of ‘sidre’ valued at 3s

4d and Stephen Cressyn, a foreigner, paid thereon 1/2d in customs duty and

2d in subsidy.” (VCH Dorset)

-

Gloucestershire, 1475 to 1485, reference to cider mill

at Rodley (TNA)

The 1349 reference is an instruction to Roger Daber, Reeve

of Surrey and Sussex, to take to Shoreham, 52 barrels and 1 pip of cider, which

is to be collected from the surrounding area. From Shoreham it must be hauled

to the docks, loaded on boats and taken to Calais. The cost of the cider was

£34 6s 8d, with each barrel costing13s 4d.

The cost of bringing it to Shoreham was 47s 2d, of keeping it in store in

Shoreham from 1 Feb 1349 to 1 April 1st (59 days) 34s 7d, taking it by boat to

Calais 115s 11d plus two recorders at port for 15days at 6d per day. The whole

cost was £44 19s 4d.

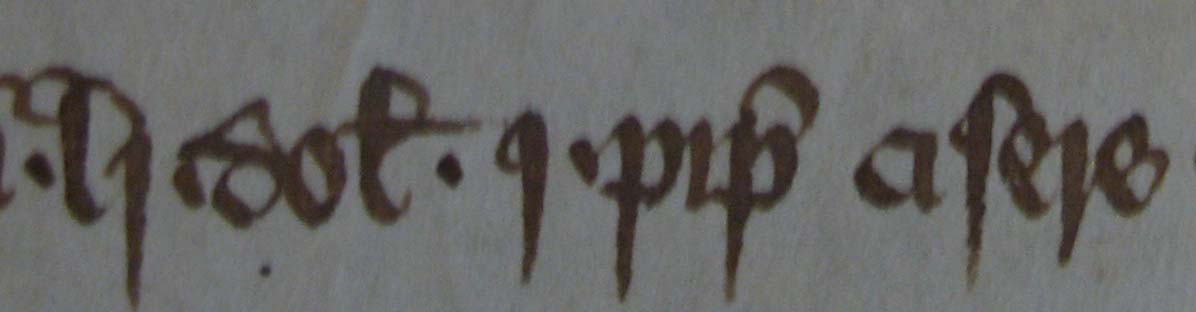

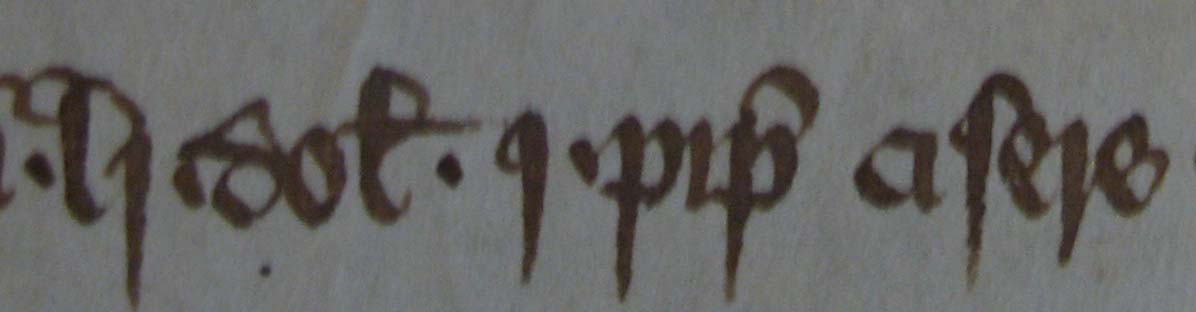

51 barrels (dol) 1 pip (2 barrels = 1 pipe) of cider (cisere); TNA document

of 1349

51 barrels (dol) 1 pip (2 barrels = 1 pipe) of cider (cisere); TNA document

of 1349

These references show cider was made and sold in England

in the medieval period, and transported for unlike beer it could be kept.. The price was between 2.5d – 4d a gallon, cheap in

comparison to wages, which were about 1d to 4d a day at this time. There are

many more references to beer than cider however (74 compared to only 2 for cider

in TNA), partly because beer was regulated by the state and the manor, but this

in itself shows how much more important it was than cider. Why was cider less

important than beer? Was it a matter of taste, of economics, regulation or

technology. Price (as today) may have had something to do with it, beer is

cheaper to make and this was reflected in the medieval price, about 0.75d to

1.5d a gallon depending on quality and area, while cider was slightly more..

Here is an explanation from Jim Franklin, orcharder in the

Teme Valley:

“Before 1900, cider was so important, so important through

the Teme valley, in Devon, in Somerset, is was a complete way of life. It was

paid as wages, it was drunk because the water was so foul and it was used for

medicinal purposes. It was taken on ships to stop scurvy, I mean it was a

complete product in its own right. Previously to, I suppose, to the 1200s

there’s reasonable records that they called it wine, it wasn’t called cider and

that’s probably where the origin came, cider went one way and wine went another

way but I cannot see really what’s the difference, between an apple being made

into wine or an apple being made into cider, it’s just that it picked up this

name and I don’t know exactly what the origins of this name is but I think it’s

supposed to mean “strong drink” but maybe it was because it was so plentiful

that it was quite a dangerous product. And it was, unless it was used properly,

a lot of people were drunk for most of their life, which is probably the best

way to go through life anyway.”

The first reference to cider in Herefordshire I have found

dates to 1400. It comes from a Court Roll for Holme Lacy held by Hereford

Record Office (AF72/10). In it Gyllam Fiensley was unjustly accused (according

to the court who fined his accusers) of entering the house of Agathe Fulfodys

and taking her bread and drinking her cider (spelt 'sizeram'). It suggests

cider was common fare of the medieval peasant in Herefordshire.

It may be that cider didn't compete well with beer, though

the trees are easier to grow than barley, crushing the apples, without the

investment of cider mills and presses probably took more work. More could

go wrong with it than beer and its harder on the stomach if drunk in quantities. Moreover beer

was taxed and regulated by the lord, so was probably more acceptable to the

authorities.

There are many more medieval (i.e. before 1500 AD)

references to orchards in the A2A (262 records) and TNA (35 records) databases

than for cider. Some of these may have been for plums or cherries, only

occasionally apple or pear orchards are mentioned specifically

The documents reveal that orchards are found all over the

country. There are more 15th century references than 14th

and more 14th century than 13th, but this may of course

only mean there were more documents not more orchards. From the 16th

century onwards however there are a huge number of references to orchards. It

seems likely that this is a reflection of the true situation, i.e. there were

more orchards not just more records, perhaps because cider was becoming popular.

Orchards were called pomerium or occasionally orto. It is

possible that some medieval ‘gardens’ were actually orchards, there are for

example one or two references to ‘a garden called orchard’,

and 'fruit from the garden' but there are many more references to ‘a garden and

orchard’,

showing that there was a distinction.

Orchards are often associated with monasteries. There are

several 13th century references to the Canterbury Priory’s orchard,

another to Kyrkested’s, a 1427 reference to Dunster Priory’s orchard, a 1239

reference to an orchard let from the abbot of the convent of Coventry, a 1405

and 1429 reference to the orchard of the Priory and convent of St Oswalds at

Wotton, Gloucester, another to the Priory of St James, Bristol, and another1203

orchard reference to Stowe Priory in Staffs.

Many medieval orchards are recorded as part of burgage

plots within towns, such as Stivichal, Bridgenorth, Chester, Torpurley

(Cheshire), Bristol, Castor, Arksey, Tavistock and others. There are several

references to orchards belonging to castles (e.g. ‘Lythirpul’ 1310 and 1368) and

halls and manors (e.g. Baddersley Clinton 1434). The death of a landlord often

led to an Inquisition Post Mortem which included a list of what belonged to the

manor. A published study of IPM documents shows that most manors had gardens,

that the largest and most profitable yielded £5 per annum, but the vast majority

were worth less than 10 shillings and some yielded no profit at all. Few

orchards as oppose to gardens are recorded in IPMs and these are mostly south of

a line from the Wash to the Severn, though it may mean that officials simply

didn't record them in the north. Gardens and orchards were probably mainly

used to supply the lord's dinner table, not for profit17.

It is possible that orchards were considered normal accoutrements to a manor, an

Inquisition Post Mortem of 1303 specifically mentions that the capital messuage

of the manor of Hunmanby, East Yorkshire has no dovecote, orchard or herbarium.

Moreover several ‘chief’ messuages have orchards (e.g. 1250 Stivichal).

Orchards also belonged to more ordinary holdings though, they formed part of

leased tenements along with the arable, meadow and pasture e.g. a 1279 quit

claim for one messuage with an orchard standing on it at Beltinge in Godmersham.

Some were apparently parts of smaller properties, e.g. in 1317 at Little

Addington, Northants a gift included one virgate

with a hovel and an orchard.

Few orchards are named,

they are mostly described in the typical medieval way in relation to other

peoples land, e.g. ‘the orchard between those of Thomas de Streta and Gunild

Taillur … extending as far as the other Forinsec orchards’ (1250, Totnes), or ‘

… between the land of Roger le Parker and the orchard of the said Thomas’ (1413

Nantwich).

The earliest references to orchards are 12th

and early 13th century, but there may well be earlier references not

listed, documents get scarcer the further back you go. A 12th

century grant records land from a demesne ‘as far back as Roberts Orchard’ in

Northants. An 1180 or 1220 (not clear) mentions a house with orchard and garden

in Gloucester; a 1200 document mentions an orchard at Hole of Parke, Devon near

a hollow way, a 1203 document refers to the Priory’s orchard at Stowe in Staffs,

a 1216 document mentions manor of Marneys Orchard in Cornwall. There are a few

other early 13th century documents.

None of the documents mention the size but this implies

they were small, for they would have been mentioned separately if they were

significant. One orchard is called ‘The Big Orchard (Huntingfield, Lincs, 14th

– 16th). There are occasional references to new orchards, such as in

1359 Bagots Bromley, ‘and a house built there with orchard and garden in Le

Thornyhall enclosed by hedges and ditches’; and in 1332 in Lincs ‘from the way

under the new orchard … also a selion lying under the old orchard’.

Most of the documents don’t describe the orchard, but

there are snippets of information. In 1385 an accounting document relating to

Harpford Manor, Devon includes the cost of hiring men for hedging and cutting

down and uprooting thorns, to hedge fields and the orchard. In Okeover, Derby a

late 13th century document lists an orchard and hedge. A 1286

document of a controversy involving the abbot of Kyrkested orders Gerard le

Breton to build a stone wall in the dyke between the orchard and grange of the

abbot and his own tofts. A 1405 document records the sale of all trees and

underwood in the orchard and grove of the manor of Foscote, Northants (TNA). A

1322 document of West Yorkshire states ‘the orchard between the garden of TT and

Matilda’s messuage on which orchard all Matilda’s sheep run’. A 1476 record

relating to an orchard in Chudleigh, Devon mentions the water courses and

springs in Tempell Orchard. A 1227 reference to St Gregory’s Priory in

Canterbury also says it has a watercourse through it. This orchard must bring a

basket of fruit to the Cathedral refectory each year showing it was an orchard

of dessert fruit. A 1376 document relating to Mayfield, East Sussex states that

if John Turner builds on his land or makes an orchard he must give a heriot

(payment on entry to property) to the lord of the manor.

There are only seven orchard references before 1500 for

Herefordshire. The earliest by far is a 1292 plea recorded at Hereford in the

Eyre Rolls against a conviction for cutting down apple trees19.

The next dates to 1413 when the lord of Pencombe Court granted Walter Wilke and

his wife a messuage 30a of land, Pole Orchard, Knakkers Croft and le

Brodecroft in Pencombe for their lives for a yearly rent of 10s.

There was an influential family called Orchard in Hereford recorded in documents

in 1403 (TNA) and 1435 when a John Orchard was a witness at Lower Bullingham.

Kings Orchard (Hereford) was recorded as a place name by 1413. An Inquisition

Post Mortem of Eton Tregoz between Hereford and Ross dated to 1420 mentions an

orchard in the assets of the lord. A rent roll for Dorstone dated 1428 lists a

perry orchard and a field called Castle Orchard showing that pears were grown

and used for perry at this late medieval date18.

A deed dated 1 December 1445 in the Hill Court Estate papers of the Trafford

family lists a messuage and orchard adjoining next Walfeldstyle being12d rent.

The earliest record for cider I have found yet for Herefordshire is

the 1400 Holme Lacy one mentioned above followed by TNA

(C115-96-6933-35) 1445-1465 bailiff accounts for Eton Tregoz manor that

refers to pressed fruit, "5s

[received] from pressed fruit of the garden of the manor there to be sold this

year". Presumably pressed fruit implies cider or perry.

We can assume from the above that orchards were known and

reasonably common in England, including Herefordshire, in the medieval period,

particularly in monasteries, manor houses, towns and castles. But most were for

dessert fruit not cider. They were small, often hedged or fenced in, to keep

animals in or out, often placed near the house. Some at least had sheep on

them. There must have been some cider orchards, scattered across England with,

possibly, more in Devon, but they were not common.

In 1588 Julian de Paulmier published his treatise on cider

in Caen, France. This was one of the first books on how to grow apples,

store and mill them and make and keep cider. It reads (in the translation

by Harold Bulmer) surprisingly modern and Paulmier like most later writers,

praises the health giving qualities of cider. His book shows orchards and

cider were well established in France in the 16th century.

In England too, from the late 16th century onwards orchards

appear very regularly in the holdings of small and large farmers alike. It

seems likely these were cider orchards and they were there to produce cider both

for drinking on the farm and selling out of county. By the mid 17th

century the Herefordian John Beale wrote:

“Very few of our cottagers, yea, very few of our

wealthiest yeomen, drink anything else (but cider) in the family save on very

special festivals”

Manor records suggest that orchards were small, one to two

acres, and many people had them. Most of the cider apples grown were different

to those of today. They would have been small, and high in tannin and like

today very varied, some types restricted to just one or two orchards.

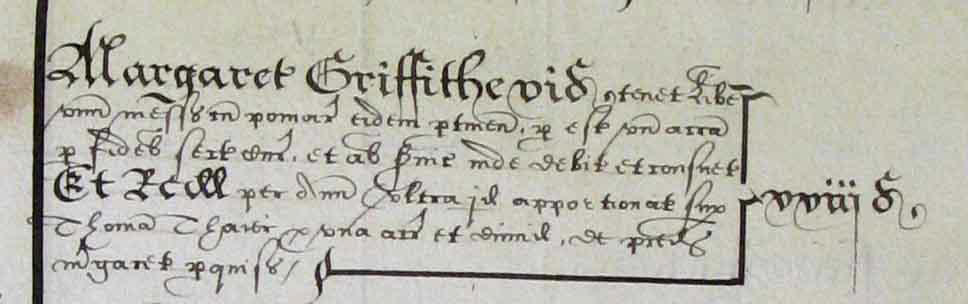

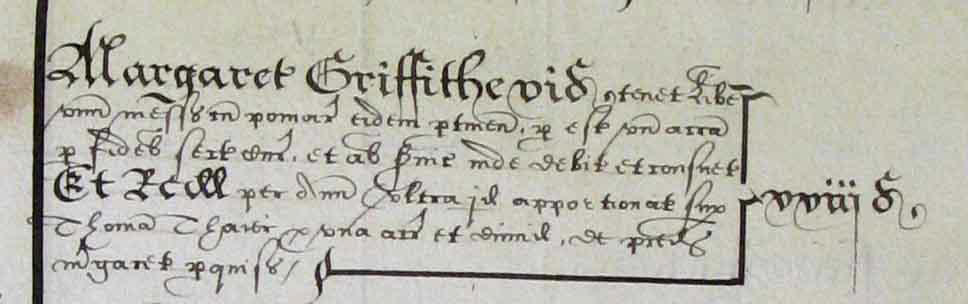

The extract above is typical. It dates to the late

16th century from Herefordshire. Margaret Griffiths a widow holds one

'free' messuage (she is a free tenant as opposed to a customary tenant,

therefore of slightly higher status and usually paying a lower rent) with an

orchard (pomar) and pays 23s in rent. She rents for one year to Thomas

Thacter one and a half acres, which is included in the rent.

John, first Viscount

Scudamore (1601–1671) of Holme Lacy, Herefordshire had been Ambassador in France

in the 1630s. During the 1640s and 1650s Scudamore developed agriculture at

Holme Lacy, including apples. He is credited with developing the redstreak

apple, acknowledged as an excellent cider apple, which spread through the county

and country.

The Herefordshire scholar and agricultural writer John

Beale (1608-1683) wrote:

“For as no culture or graffs will exalt the French wines

to compare with the wines of Greece, Canaries and Montefialco, so neither will

the cider of Bromyard and Ledbury equal that of Ham Lacy and Kings Capell in the

same small county of Hereford. Yes the choice of Graff or fruit hath so much of

prevalency, that the red strake cider will every where excel common cider as the

grape of Frontignac, Canary or Bacchareach, excels the common French Grape, at

least till by time and tradition it degenerates”.

“… a row of Crab trees will give an improvement to any

kind of Perry and since pears and crabs may be of as many kinds as there are

kernels, or different kinds or mixtures of soils, in general character I would

prefer the largest and fullest of all austere juices.”

He goes onto say that soils are very variable, as our the

fruit of crabs, apples and pears. Having tried cider for 30 years in

Herefordshire, Somerset, Kent and Essex he thinks the best cider comes from the

hot Rie Landes. … the right cider fruit generally called Musts, there is a red

strakd must, meriot. It is worth noting that Beale was a relative of Scudamore

and was probably biased and that the writing that is left to us comes from a

select band of educated men, who all corresponded with each other.

John Evelyn was a famous diarist and agricultural writer.

He knew several landowners in Herefordshire including Scudamore and Beale,

quoting them in his work. In 1664 John Evelyn in his commissioned book ‘Pomona’

says:

“Seeing a cider orchard is but a wild plantation, (it is)

best in arable, well enclosed from beasts, and yet better on the tops of ridges

and natural inequalities (though with some order as we shewed). Fencing single

trees used to be done by rails at great charges, or by hedges and bushes which

every other year must be renewed and the materials not to be had in all places

neither. I therefore prefer and commend to you the ensuing form of planting and

fencing which is more cheap and easie … ”

He goes on to recommend digging out turf around the tree,

laying it like a pyramid around the tree and planting with briars or thorn on

top.

“Plant the crab stock in October 32 foot distance, not

graffed till third spring. If your design be for orchard only, interval of 16

foot for dwarfish kind, provided the ground be yearly turned up with spade, and

the distance quadrupled where the plough has privilege.”

“I have seen a calculation of 20 fruit trees to every five

pounds of year rent. … Had all our customs and waste lands one fruit tree but at

every hundred foot distance, planted and fenced at the public charge for the

benefit of the poor … would afford them a most incredible relief. And the

hedgerows, and champion ground (open arable fields), land divisions, mounds and

head lands (where the plough not coming it is ever abandoned to Weeds and

Briars) would add yet considerably to the advantages without detriment to any

man.

Evelyn mentions several varieties of apple including Red

Strake, especially the Irchin field (Archenfield) Red Strake (see Scudamore

above), Genet Moyle, Bromsbury Crab, White Must, Bexyd Hery a musky pear, and

the French Kernel, a tree of small of growth and empty, meer skins of kernels

“not unlike to the emasculated scrotum of an eunuch”. He says the Horse Pear

and Bear Land Pear are the best and one tree can produce 3 or 4 hogshead.

Evelyn recommends planning orchards using crab stocks,

planted in October 32 foot distance, and graffed in the third spring. This wide

spacing was for a grazing orchard but “If your design be for orchard only have

an interval of 16 foot for dwarfish kind, provided the ground be yearly turned

up with spade, and the distance quadrupled where the plough has privilege”.

From the 17th century to the present day

orchards seems to have gone through periods of enthusiasm and expansion,

followed by decline and neglect. The neglect was brought about by a range of

factors. The cider tax of 1763 to 1766, strong advertising by the beer lobby,

and the comparative cheapness of beer that relies on a yearly crop rather than

trees that take six years to produce have all been blamed, but fashion and taste

must have always been strong factors. The 18th century glass and porcelain

collection at the Cider Museum shows that cider was promoted as a special drink

for the upper classes, as well as a drink for working people

|

|

|

| Meissen 18th century |

18th century cider glass |

17th century cider glass |

The late 17th century was a high point for

cider and orchards, partly inspired by the Redstreak apple. In the 18th

century, for various reasons, if we can believe the agricultural writers, it

declined again. In the mid 18th century cider glasses and porcelain

ornaments, beautiful enough to grace the most aristocratic tables show cider was

at a high point. Its was promoted as well by the wealthy horticulturalist

Thomas Andrew Knight (1759 to 1838) of Downton. He published a Treatise on

Cider in 1797 and in 1811 the Pomona Herefordiensis, which describes locally

grown cider fruit and pears. In 1786 he began grafting and breeding fruit

trees.

What would orchards have been like in those days? It

seems as though they were varied, with different areas having different trees.

There were many, many types of apples and pears. Presumably they had developed

from seedlings for the most part, and those that proved to be useful were

propagated and preserved. Certainly the techniques for doing so were known and

publicised.

The late 19th century seems to have been a

period of decline for Herefordshire cider and orchards. The researches of

Robert Hogg and others in the late 19th century published in a Pomona

led them to the conclusion that:

“Many of the most valuable fruits of the last two

centuries … were either all together lost, or had almost disappeared from the

orchards. The following varieties, which formerly were very highly esteemed,

may be mentioned as examples, viz: Woodcock; Friar; Pawson; Oaken Pin; Arier;

Olive; Coleing; Whitesour; Blackamore; Mydiate; Dufflin; Meriod Ysnot; Lings;

Dena’s Apple; Peasantine; Heming; Westbury Crab; Bromsberrow Crab; The Stocking

Apple; Underleaf; Best Bache; Great White Crab; The Redstreaks; Summer, Winter,

Yellow Moregreen and Red, White, Red and Green Must; Summer and Winter Fillets;

Elliott; Devonshire Royal Wilding; Gennet Moyle; Hagloe Crab; Forest Styre;

Skyrme’s Kernel; and Foxwhelp. The neglect to cultivate these valuable

varieties is, doubtless, very much to be attributed to the prevailing belief,

that ‘Sorts die out of necessity’ , or, as Mr Thomas Andrew Knight expressed it,

‘There was no renewal of vitality by the process of grafting, but that the scion

carried with it the debility of the tree from which it was taken”.

The Pomona Committee managed to raise several Foxwhelp,

Skyrme’s Kernel and Taynton Squash.

As tastes and technology changed new varieties were

introduced, many are called Norman, as they supposedly derived from Normandy.

It seems that any bittersweet has the name Norman attached to them, so the taste

for bittersweet cider may date from this time. There are at least 20 different

‘Norman’ types. The Woolhope renamed them ‘Hereford’ leading to the following

varieties

-

Black Hereford

-

Broadleaved Hereford

-

Brown Hereford

-

Cherry Hereford

-

Green Hereford

-

Handsome Hereford

-

Hereford Bittersweet

-

Hereford Redstreak

-

Red Hereford

-

Spreading Hereford

-

Shortjointed Hereford

-

Square Hereford

-

Strawberry Hereford

-

Sweet Hereford

-

Upright Hereford

-

Yellow Hereford

Apple Varieties, Cider Fair, Leominster

2004

The Tithe Commutation act of 1838 led to the first nation

wide survey of land use since Domesday (1086). The survey recorded land use and

rents over much of the country, in Herefordshire about 80% of the land was

survey. Sadly this huge amount of information hasn’t been digitised. The tithe

field names however have

and they give an indication of the extent of apples and pears in the county.

There are 14,759 fields called orchard in Herefordshire in 1840 out of a total

of 123454, this represents 12% of all fields. They are spread all over the

County fairly equally with concentrations in central Herefordshire around

Hereford, north of Bromyard, in the south east and the Wye Valley. There are

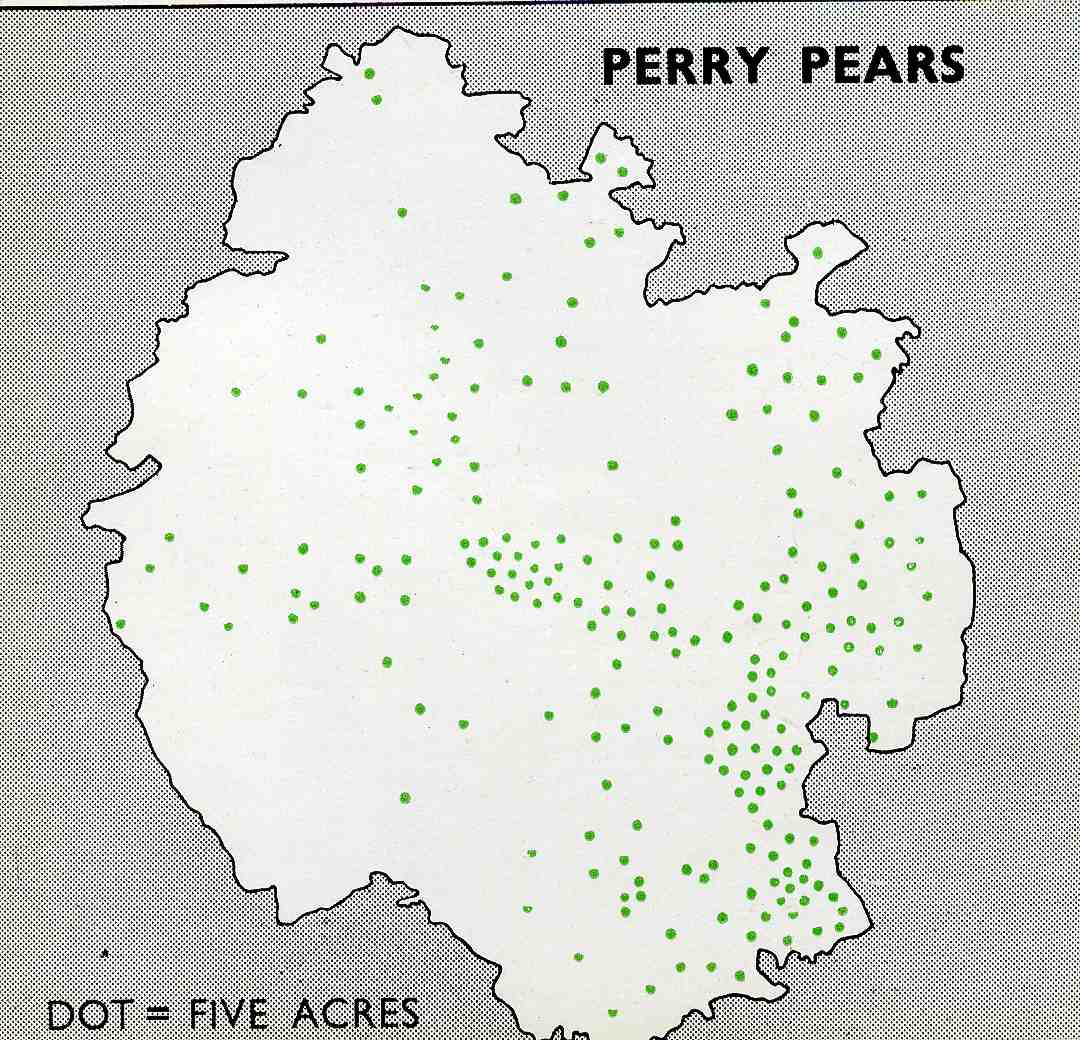

150 ‘perry’ field names, they are found in 48 parishes (of 256) with a definite

distribution on the east and south of the county.

Orchards in recent years have decreased in extent. This

is partly because yields per acre have considerably increased. A period of

decline that began before the last war led to Bulmers beginning planting schemes

in the 1950s and 1960s. With some set backs orchards are now on the increase

due to the success of cider sales in recent years.

Table: Acres of Orchard in England and Selected

Counties

Top of Page

|

County |

1877 |

1880 |

1883 |

1936 |

2005 |

|

England |

159,095 |

175,000 |

185,782 |

106,668 |

|

|

Herefordshire |

24,885 |

26,683 |

27081 |

20,267 |

13,560 |

|

Devon |

24,776 |

25,758 |

26,348 |

|

|

|

Somerset |

20,291 |

22,993 |

23,407 |

|

|

|

Kent |

13,097 |

14,685 |

17,417 |

|

|

|

Worcestershire |

14,621 |

15,854 |

16,804 |

|

|

|

Gloucestershire |

11,965 |

14,178 |

14,926 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

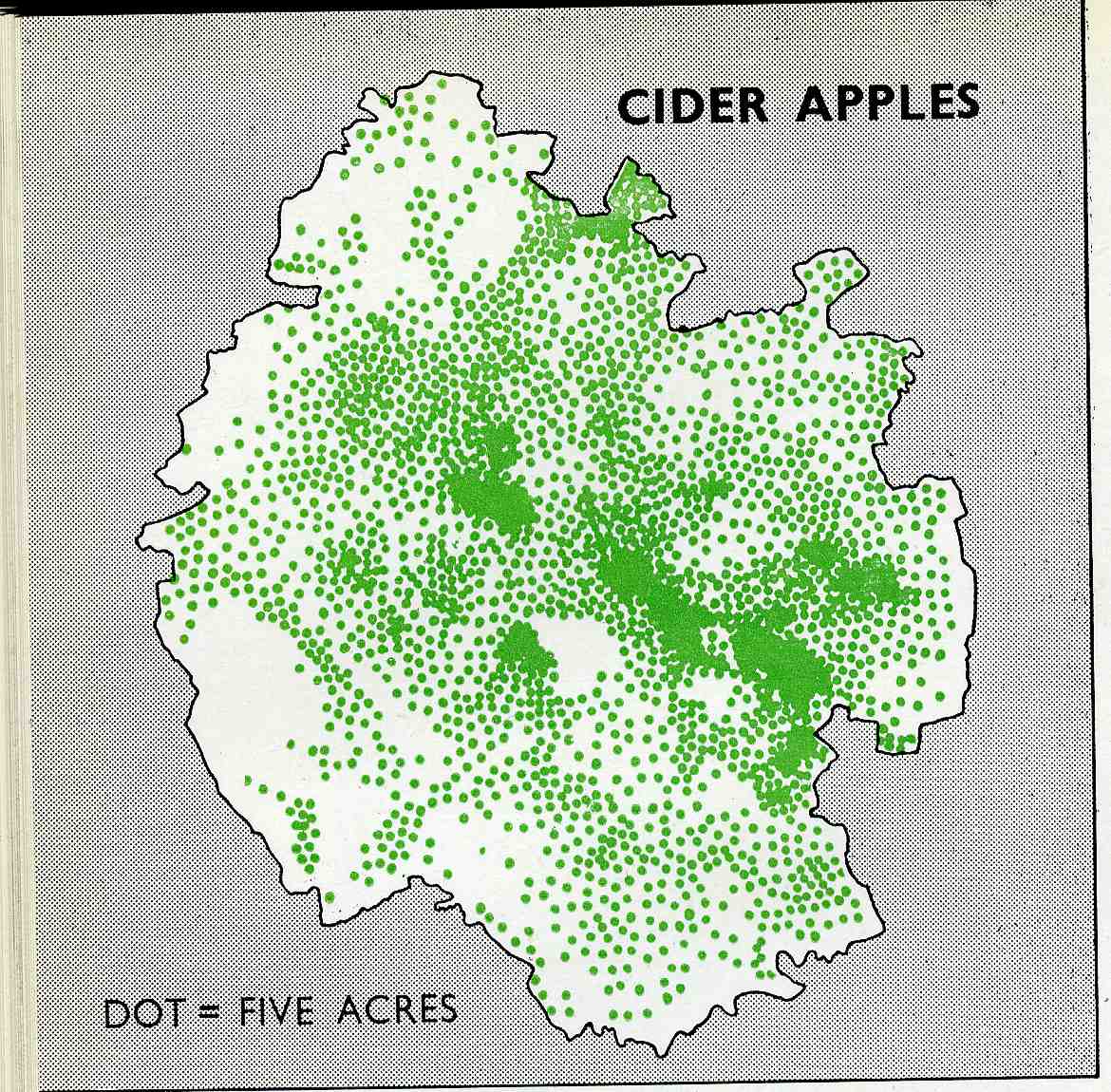

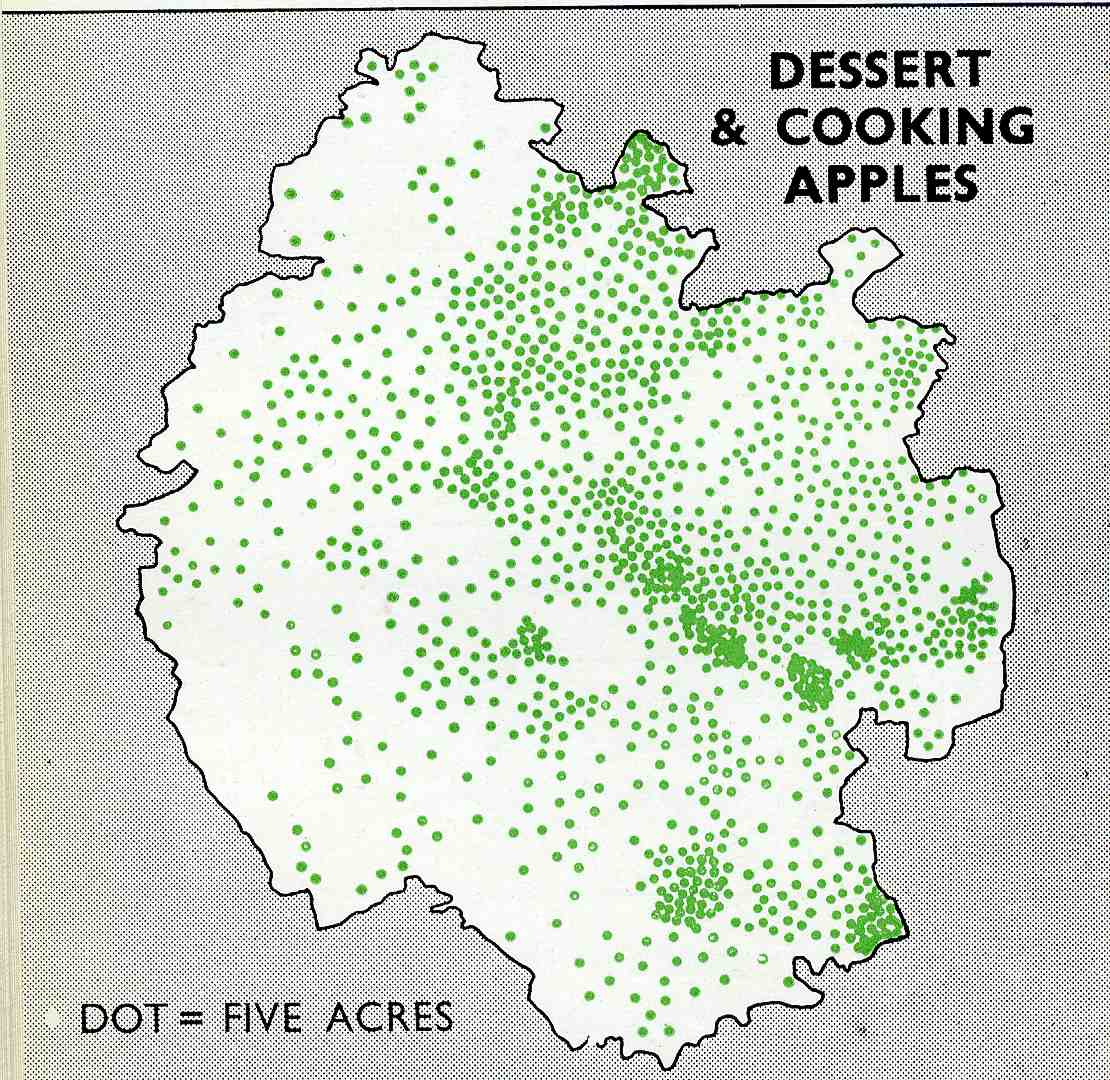

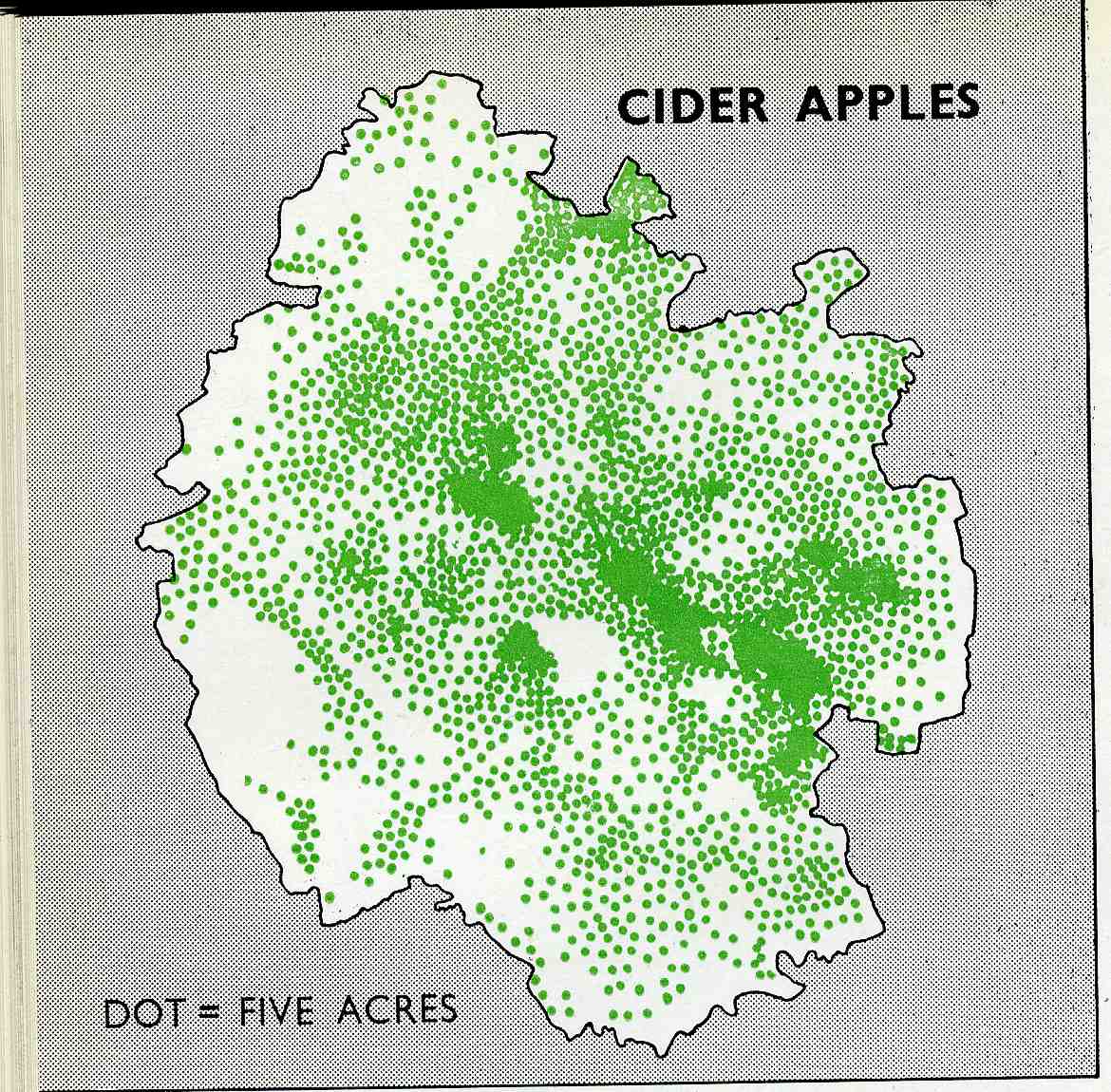

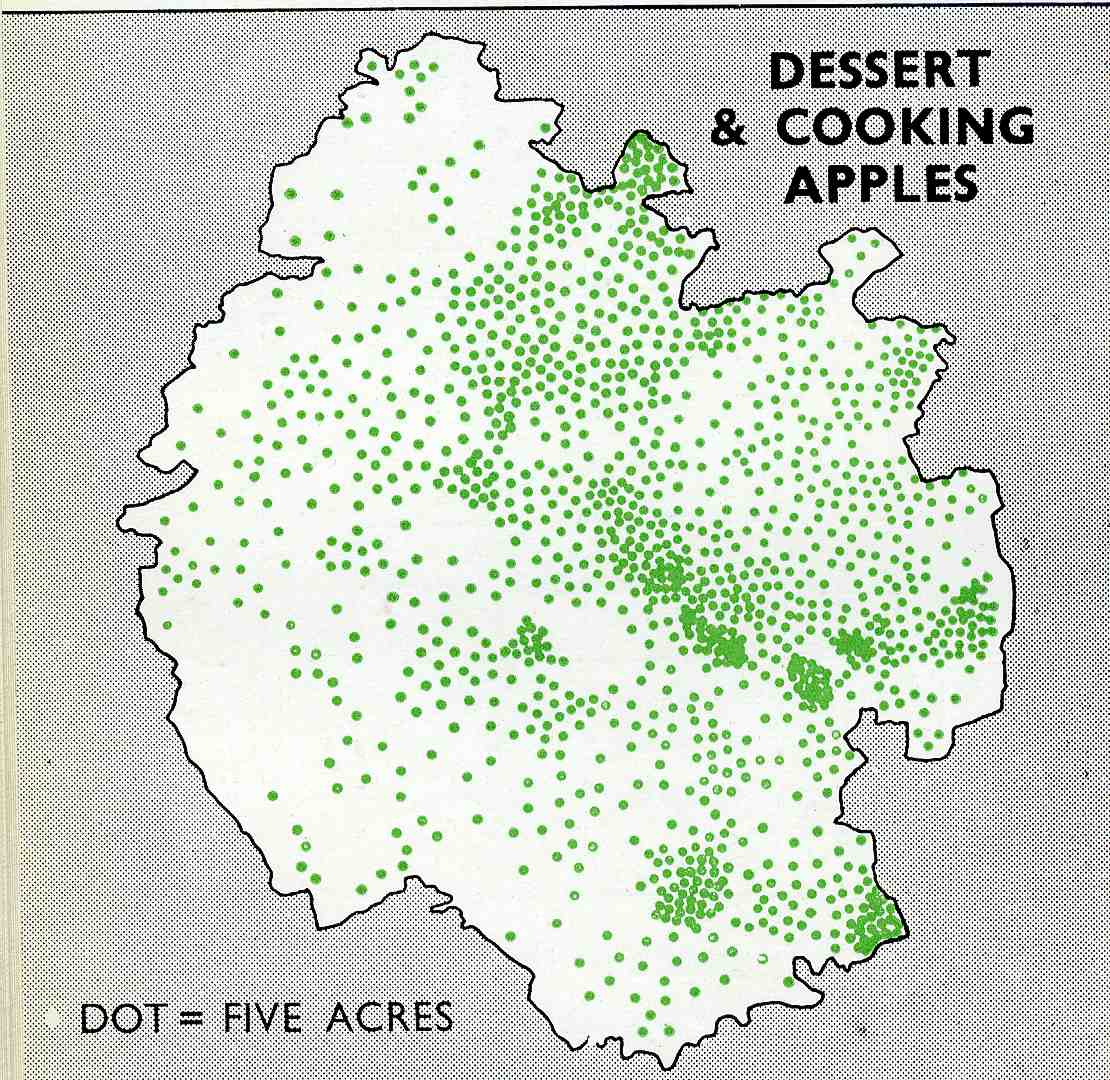

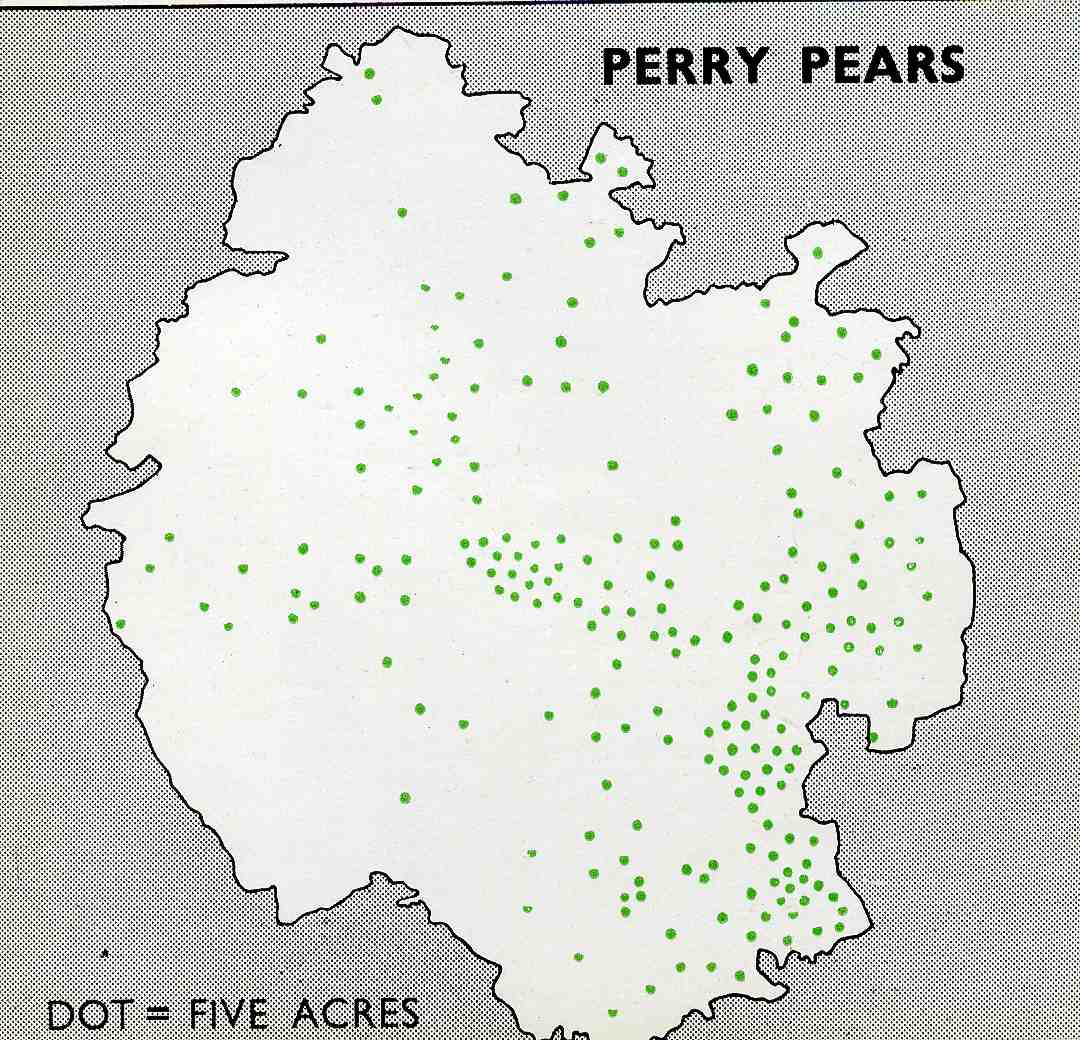

Distribution of cider and desert apples and perry pears in 1934, from 'A

Planning Survey of Herefordshire' (1946)

Planting an orchard has changed according to technology and

economics. In the past orchards were planted so animals could graze below them

or crops be grown. It was considered advantageous to stretch the period of

apple picking as much as possible. With factory cider things changed, the

factory pushed growers to maximise production. Mechanical harvesters and

shakers were invented, sprays and new varieties of apples. Trees now needed to

be closer together, the ground level for machinery, the harvest times reduced to

September to December, so early not late varieties are required. Much of the

change in modern orchards has been under the guidance of the research centre at

Long Ashton, Bristol (now closed see Archive pages).

“In the Teme valley the clay soil was too heavy for a

horse to plough even an acre a day so the Teme valley was mainly used for hops

because once you’d planted a hop vine it was there for twenty years and orchards

because once you’d planted an apple tree it was there for a hundred years and

Hereford cattle which would graze on the grassland. So people used these three

crops, hops, apples and beef with sheep on the higher ground. When the tractor

came along it would plough five acres a day and now I don’t know what it is,

it’s probably sixty acres a day.

They were usually planted at forty trees to the acre and on

some varieties they would be twenty trees to the acre. They always took into

account the nature of the tree whether it liked south facing whether it could

stand a north wind whether it could stand a little bit of wet from the west so

if you looked at the very old orchards of which there aren’t many left, the

particular tree that was planted on the west side would protect the trees on the

east side from the wet and the same on the north protecting the trees on the

south which were a bit more tender. So it was thought out and documented very

well. When they were established of course you could graze under them so it was

a dual crop you’ve got your orchard and then you’ve got the grazing of the

cattle and the sheep and of course what came into another income was the

mistletoe in the Teme valley and after twenty years/thirty years trees would

have a lot of mistletoe so they had the benefit of that plus firewood.”

Jim Franklin, orcharder, Teme Valley,

Herefordshire, 2006

“I always remember there being corn with the trees

between. The bush orchard, the trunks are lower, more shade and is not suitable

for ripening. But the standard trees are taller trunked. After the war our

orchard was put back to grass, there were ridges from the plough between the

trees, because you could only plough one way, it didn’t matter when you were

picking by hand, but when you came to mow them, you had to try and level it out

because the mower hit the bumps”.

Gillian Bulmer, orcharder, 2006

“Some of the trees when we came in 1930 they’re still

there now and they look no different. It’s unbelievable really that we have one

apple tree which I know was hollow because I used to find bird’s nests in there

when I was a young lad. It’s in the hedge, it’s completely hollow but it still

bears fruit at this time and that is, as I say well seventy six years ago. So

you can see how long those trees have been there – well hundreds of years.”

Kenelm Johnson

“In 1970 when I first came to Hereford the average crop in

this county was 2 ½ or at the very best 3 tons an acre. Traditionally apples

were planted 40 trees to the acre. The best crop I ever saw from a standard

orchard was 4 tons after ten years. That’s a life time. What we did at that

time, we changed the shape of the tree, instead of having a big open tree, we

grew centre leader trees like Christmas trees, more trees per acre, no grazing

animals underneath, more and smaller trees on semi dwarf root stocks. This was

all pretty leading stuff. It hadn’t been done much before, and it was done with

the help of Long Ashton. My main job was to get the Incentive Scheme off the

ground, to get farmers to plant reasonable size orchards, say 20 acres, on long

term contracts, 20 years, with bush trees. We were planting at 180 to the

acre.”

Jon Worle, orcharder, 2006

“The Dabinett are the most profitable they are the

heaviest apple, the Michelin crop well but they are light. You can get 29 ton

of Dabinett on an artic lorry but you can only get 24 ton of Michelin. They pay

by weight. Dabinett produced 25-26 tons/acre this year on 14 acres, this is

good. Its been a light year, we had a very wet spring, at that time most were

in blossom, the wet got into the blossom and caused them not to set, then we got

the dry period and caused them not to grow. Strangely it suited the Dabinett,

the average for Dabinett is between 20 to 26 tons acre. The Somerset are

biannual, next year I am expecting 400 tons from 18 acres, that’s the good

year. We have worked it out roughly between 16 to 18 tons/acre all over the

orchard. … ”

John Moss, Manager

Rowley Orchard, Leominster, planted under Bulmer’s Incentive Scheme

“The full standard orchard would stand for 150 years,

though some of the trees wouldn’t go that long, but we had a tree on our land

which was planted in 1860 and that just about died in the 1970s, that was a long

time for a tree to produce fruit. It had got a lot of disease with it but it

still carried on going. … The half standards came in and that was still used for

grazing underneath but cattle would normally eat the branches of a half

standard.”

Jim Franklin

“The original Bulmers incentive scheme was a result of an

increased demand for cider and the fact that the supply of apples from Normandy

and Brittany was not very reliable. The scheme was a great success. Originally

the acreages were very small by today’s standards, 5, 10, 15, 20, perhaps 30

acres for outside growers but it was a new venture for them. … In the early

1990s we saw from our first generation of orchards that 20 years was probably

not long enough because it would take anything from between 6, 8 or 10 years to

reach full cropping and then they would only have 10 years of extra contract;

hence we offered 30 years and farmers were very happy with that. When you start

talking of 30 years, it’s a very long time in any business, in industrial terms

companies don’t survive that long and certainly don’t carry on making the same

product for 30 years.”

Chris Fairs, Bulmers

“There’s red spider comes in, you have to keep control of it.

That will lay its eggs in autumn, it will over winter in trees, you usually walk

through about March time with a magnifying glass to see if you’ve got any. You

get rust mite, it will over winter, there is sucker, another pest, there’s rosy

apple aphid, that’s another one. There’s blossom weevil, that over winters in

the soil, as soon as you get the warm weather in spring, it will start to walk

up the trunk and lays a maggot just as the flower is forming, at ‘mouse’s ear’

stage they call it, it will lay the maggot into there. As the flower

progresses, when the flower drops off, you can see the duff flowers, the maggot

is inside. As soon as you get a bit of warm weather, go round with an umbrella,

hold it upside down and hit your tree. You will see your weevil then. Then you

spray then.

You only spray when you’ve found you’ve got them, but if they

are in one tree they are usually all over.

Another pest is saw fly, which comes when 80% of petals have

dropped. You could put up traps for that but we usually spray for that it, it

causes the apple to go rotten on the tree. Apples and plums can survive them

but they cause brown rot.

I have more or less eradicated red spider at Rowley. I use

sea weed. I spray Maxicrop, when the leaf comes on the tree I use a pint to an

acre seaweed on the trees, mixed in with my other sprays. It feeds the tree,

some people doesn’t reckon it does any good, but an old campaigner at Bulmers

used to use, so I though I would try, and ever since I’ve used it we don’t get

red spider. And that’s a good thing because red spider spray is really

expensive, its £140/litre. You dilute it down to 5 fluid ounces an acre, it can

run to £2000 at Rowley, plus all the work. So seaweed runs out at £9/acre all

through the season. Liz Copas has been doing research into it over ten years

and she reckons it helps with mildew as well. If you’ve got a healthy tree, its

going to fight mildew.

We feed the tree with potash, about 3.5 cwt of potash to the

acre in March time. That is done with a fertiliser spinner. About the end of

June I go through with 1 cwt to the acre Nitrogen, it helps a little bit of new

growth and the leaf green. We put it on with a spinner, a ‘bander’, we just put

nitrogen onto the bottom of the tree. The potash we put all over the ground.

Then the sea weed. We never irrigate, it would be very costly.

Since I’ve taken over up at the orchard I don’t spray my

hedgerows, with herbicide, I tends to let my nettles grow all round the

hedgerows, the beetles and other pests come out of that into the trees.”

John Moss, Rowley Orchard, Leominster

“I have nine acres in orchards growing round the Teme

valley. That is very small and unprofitable if you take into account that you

have to buy new equipment. I’m normally mending old equipment and keeping it

going because the financial profits aren’t there to buy new equipment. We are

trying to turn it round to a semi organic system and reduce the input of sprays

mainly because they need expensive equipment and for a small orchard it is not

very practical, so we’re using other ways to control pests. … As a commercial

orchard we have to use insecticides and fungicides. Over thirty year I’ve seen

an enormous change. In the first ten years it was a complete programme of

spraying. On a certain day you went out and sprayed and killed everything that

was in sight, this was due mainly to lack of knowledge and sprays weren’t

expensive, so it was a blanket kill and you kill the predators and you kill the

pests. … If you’ve got a batch of predators in the surrounding areas, in the

hedges and trees, they will move in to eliminate the pests for you, as that’s

what they live on. If you eliminate the pest then you kill the predator because

he dies of starvation. But you do have to have a balance, you look at the tree

and it’s got a pest on yet it isn’t doing much damage and the predator will then

move in. … Its always been difficult, you get up at five in the morning to look

to see if the pest has increased and if it has then you’ve got to spray”.

Jim Franklin, 2006

“Orchards provide a unique habitat in Britain, one of ‘open

growth’ that is, trees in grass. You don’t find this anywhere else, our climate

and agriculture means we either have woods with a shady habitat, or open arable

and grassland, with a shade-free environment. In other parts of the world, in

hotter drier climates, an open growth habitat would be normal, the heat inhibits

vegetation progressing to full shaded wood. So in orchards we might expect to

find more continental type of insects. Another feature of orchards is dead

wood. Dead wood supports a host of insects (and animals that feed on them), so

if orchards aren’t kept too tidy they will attract a range of different

insects, birds and mammals.” Jon Cooter, Beetle Specialist, Herefordshire

Open growth habitat in 50

year old orchard.

Thousands of blossoms for insects

Dead wood is a favoured habitat of many insects in England, it

is estimated 1,800 species of insect depend on it. Insects are of course

important food sources for other animals and pollinators for plants. Apple

trees are short lived, within 100 years they will be declining, so an orchard is

likely to have more dead wood within it than other habitats.

The blossom, fruit, wood and grazing areas between trees all

provide food and habitat for a range of creatures. Blackbirds, redwings,

thrushes and field fares feed on the fallen apples. Mammals such as badgers,

foxes and mice will also pick up fallen fruit. Standard and also the old bush

orchards use minimal spray and fertilisers will be colonised by wild flowers

such as bluebells and orchids. Some beetles, moths and birds are

peculiar to orchards. These include mistletoe which

grows primarily on apple trees and poplars and occasionally on other trees and

its companion the Mistle Thrush which feeds on mistletoe and spreads its seed by

wiping its beak clean of the sticky fruits on perching posts.

“Mistletoe was purposely planted. Some of the old chaps

when I was a boy in the forties would collect seed in December to see if it

would grow. It wasn’t done as a crop it was done purely out of interest to see

if they could get it to grow.” John Franklin

Mistletoe in January 2007, Humber, Leominster

Mistletoe is common

in Herefordshire, more so than most counties, and has some rare insects

associated with it. In 2000 the beetle Ixapion variegatum ‘the Mistletoe

Weevil’ was discovered new to Britain in a Herefordshire orchard. Some effort

was made to find this species during 2003’s survey work. It turned up during

the visit to the orchard near the Nature Trust’s Lower House Farm and also,

during the summer, at Mordiford. The Mistletoe Tortrix was named after

Mr Woods, a Herefordshire entomologist of the late 19th century. It is rarely

seen, very mobile, flying at the hottest time of the day.

The Gnorimus nobilis, the ‘Noble

Chafer’, is a spectacular beetle, normally only detected from its dropping,

but if you are lucky you may see it feeding on Giant Hogweed (if allowed to grow

between apple trees). The account below is by Jon Cooter who has been

surveying the Noble Chafer in Herefordshire for several years.

The Noble Chafer Gnorimus nobilis,

Breinton Orchard Early Purple Orchid (Orchis

Mascula), Breinton Orchard

Its present day strong hold of Gnorimus

nobilis, the ‘Noble Chafer’ includes parts of Hampshire (New Forest),

Herefordshire, Worcestershire and Gloucestershire. There are also recent records

for Oxfordshire. During the earlier part of the 20th century it was

well known from orchards in Kent, many of which disappeared as the suburbs of

London expanded. Older entomological literature includes records from as far

north as Carlisle. Gnorimus nobilis is, by British standards, a large

beetle (typically 15 – 20mm from front of head to tip of the elytra (wing

cases)). It is always bright metallic green with a varying number of small

white markings – these are cuticular secretions and can be chipped off; rarely

they are totally absent. The beetle breeds in the rotten interiors of a variety

of trees including oak and willow, but is best known in Britain from fruit

trees, plum, cherry and apple in particular, but also perry pear. It seems to

prefer open growing trees rather than those in forest. Possibly such trees

receive more heat from the sun creating a warmer drier interior to the host

trees. The larval stage typically takes two years from egg to maturity. The

full grown larva stops feeding during the autumn, eats out a cell within the

rotten wood and pupates in a flimsy cocoon during late April/May and adults are

to be found from late May through to August with the majority of sightings

during June.

The adult is capable of rapid agile flight and visits

flowers to feed on nectar; pale coloured flowers such as hogweed, elder and dog

rose are preferred. There is evidence that some adults never leave the hollow

rotten trees in which they spent their immature life. The adults frequently

pair inside the tree and the female will deposit her eggs in the same tree that

she ‘grew up’ inside. Gnorimus nobilis lays very few eggs, possibly as

few as 20 per adult.

The only British beetle likely to cause confusion is the

‘rose chafer’ Cetonia aurata. The ‘rose chafer’ is more elongate and has a

smoother metallic green upper side; in Gnorimus the metallic green has a

‘frosted’ appearance. This is a difficult beetle to survey. It can be found

infrequently on flowers in orchards and woodlands where it breeds. Another good

method of ascertaining its presence is to look for larval faecal pellets.

Needless to say care must be taken not to damage the host tree; breaking open

rotten boughs and trunks will destroy the beetle habitat completely.

However, very often there are loose flakes of rotten wood

at the base of the tree, at a fork or where a branch has broken off. The larvae

seem not to make tunnels in the wood like many other wood-inhabiting beetle

larvae but live in the lose debris inside the rot cavity where they feed on the

hard rotten wood.

The chafer does not bore into the wood like so many timber associated insects.

Rather it is like a miner sitting in a cavity eating away at the fungoid wood

forming the sides. It goes for trees “attacked” by the fungi Laetiporus

sulphureus, a fungus that attacks the cellulose of the trees cells resulting

in ‘red rot’ and Inonotus species which attack cellulose and lignin

components of cellular tissue resulting in ‘white rot'. The faeces or

‘frass’ is moist when deposited but dries out forming discrete hard pellets.

These are generally lighter in colour and always much larger than the frass made

by woodlice. The faecal pellets can spill out of a cavity naturally or when a

section of the rot is removed. Frass can be looked for at any time of the year

enabling survey work to be undertaken at any time. It is possible to

distinguish the older dry and fresher ‘moist’ frass. Generally older frass is

darker and harder. The ability to do so will help establish if there are larvae

present or if they have been present in recent years. The latter is useful and

might simply indicate a tree has been abandoned with the likelihood of other

trees in the vicinity now being utilised.

Larval workings are often evident (inhabited trees) in the

exposed hollow cavities or if a tree is cut up for firewood. The surfaces are

clean and smooth, very distinctive (just believe me, they are!) quite unlike the

larval workings made by other wood inhabiting scarabs and Cerambycidae (longhorn

beetles).

Gnorimus should be looked for in orchards of older

standard trees. Modern trees on dwarf rootstocks or recently planted young

standard trees are not suitable. However, if mapping and recording orchards,

these modern orchards should be included. Do not forget, dying and dead

trees can be used for several generations by the ‘noble chafer’.

Data gathered so far

from the People’s Trust for Endangered Species (PTES) funded BAP survey in the

three counties has shown Gnorimus to inhabit trees with breast height girth

between 0.62 and 1.16m. Of thirteen trees found to be harbouring the beetle in

Longhope and Blaisdon parishes (Gloucestershire) twelve were plum and one

apple. (It has been estimated on field evidence that 90cm BHG approximates to

100 years of growth; this is not proven and will be affected by a variety of

factors – tree virility, position, soil etc). Hereford Nature Trust’s survey

work in 2003 detected larval frass in approximately 22 trees at four locations;

partial remains of an adult beetle was found amongst frass in an orchard at

Yarpole.

Apple trunk with insect emergent holes, Woolhope

Woodpecker nest holes in orchard, Woolhope

Apple is a good food plant for common moths but if you run

a light trap below apples it is very quiet, for some reason you don't catch many

moths. There is the Apple Ermine moth,

which lives in communes within communal webs. There are thousands of them in

orchards. The web protects the caterpillars before pupating, but there are some

doomed larvae that have parasites that wrap their more fortunate siblings in a

final big

cocoon.

The Eyed Hawkmoth is often in orchards as well as other

habitats, it is in decline. The Red-belted Clear Wing, likes older types of

trees as the caterpillar moves straight from the egg to under the bark. It is

quite common in Herefordshire. The Mistletoe Tortrix is a rare moth associated

with orchards. A micro-moth Ypsolopha asperella last recorded in the

late 19th century, was found specifically in apple in Dorset and

Herefordshire. A few micros feed on leaves, there is Stigmelada mallela,

a declining species. It makes a blotch on the leaf and Inconditella

which used to be called pomella. Mike Harper,

Moth Specialist, 2006

Apple Moth, 18th century cider glass

J E T Rogers, huge

1866 survey of prices (A History of the Agriculture and Prices in

England) found a 1276 reference of cider at 3d/4d a gallon. We don’t

know how big these 51 barrels were, coopers terms are a pin 4.5 gallons,

a barrel 36 gallons, a hogshead 54 gallons. If a hoghead at 3d/gallon

it would be 13s 6d, the same price as here, suggesting the barrels were

hogsheads of 54 gallons. However hogsheads sometimes meant twice

this size, see note 13 below. In 1885 W Price, a cider maker in

Hereford was selling a Hog of Cider of 102 gallons at 5d a gallon

(Archive of Cider Pomology 13/1/136). So his Hog was twice the

size,

HRO A63/I/1-23 O/M63,

It is interesting to note that there were many orchards in Pencombe on

the 1840 tithe map, though none were called Pole Orchard at that time.

Bull, Dr H G and Hogg

Dr, 1875-1885, The Herefordshire Pomona, The Woolhope Club, 2 Vols

Of this traditional

orchard: 5385 acres. These figures were calculated as a result of

mapping by students (2000-2005) for the Millenium Map, held by

Herefordshire Biological Record Centre.

17

B M

S Campbell and K Bartley, England on the eve of the Black Death: an

atlas of lay lordship, land and wealth 1300-49, Manchester University

Press, 2006.

18 TNA SC11/258

19. Jakeman and Carver Directory 1902 page 21

referring to TNA Eyre (Court) Rolls

Home

Top of Page

History of Cider

51 barrels (dol) 1 pip (2 barrels = 1 pipe) of cider (cisere); TNA document

of 1349

51 barrels (dol) 1 pip (2 barrels = 1 pipe) of cider (cisere); TNA document

of 1349